Trees and Serpents: Ancient India’s Living Landscape

670. Introduction and Stupa Drum Panel with Naga

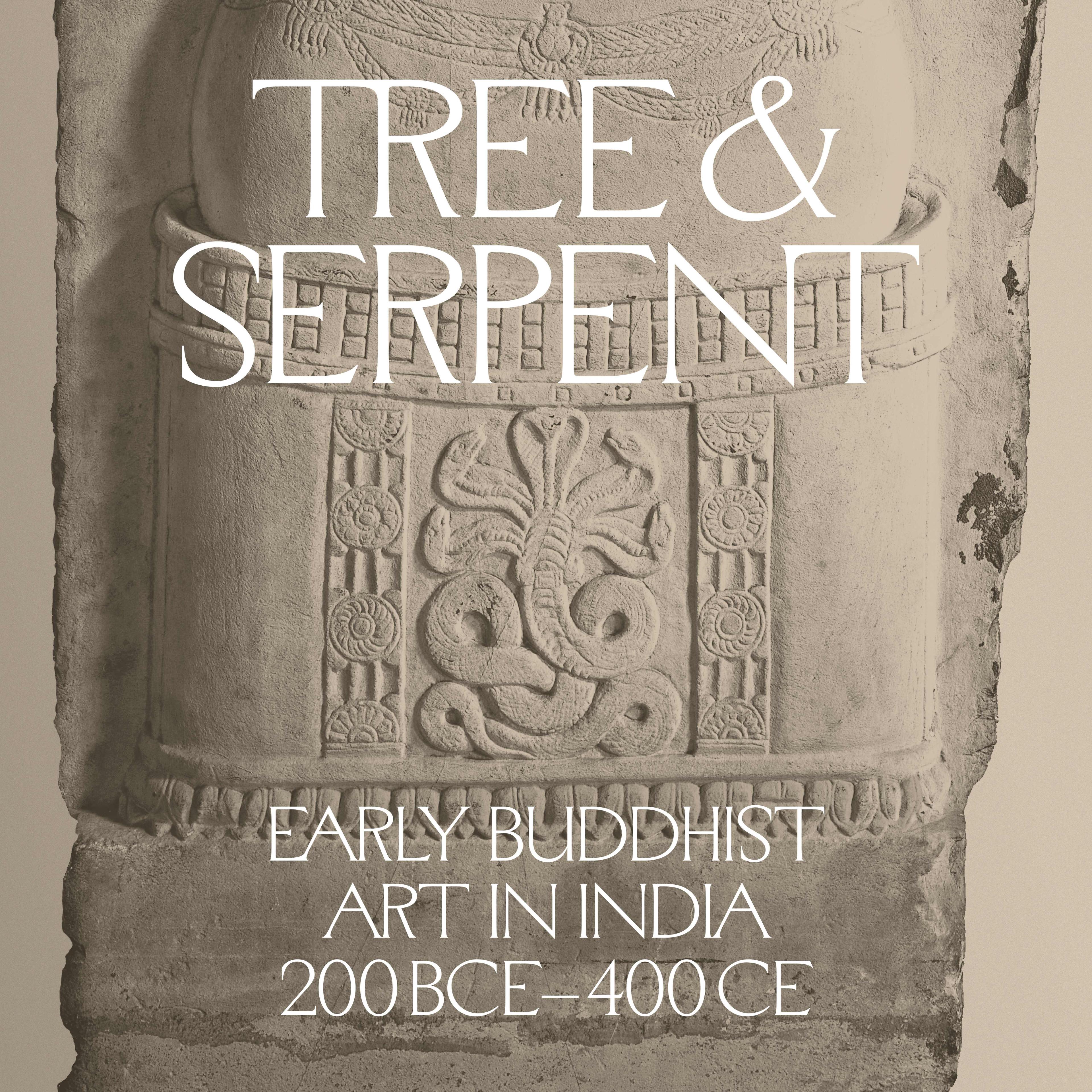

NARRATOR: Welcome to Tree & Serpent: Early Buddhist Art in India, 200 BCE to 400 CE. This exhibition showcases rarely seen objects from the Deccan in Southern India, representing the origins of Buddhist art.

JOHN GUY: When Buddhist art appears in India it’s sophisticated, complex, iconographically elaborate, and embedded with great stories, great narratives. It doesn’t come out of nowhere.

NARRATOR: These stories are told through imagery from an incredible sculptural tradition that existed long before the introduction of Buddhism in Southern India. In the grand piece before you, you'll find a multi-headed serpent under the cover of a tree. To help us understand the role of trees and serpents in this particular cultural and religious context is John Guy, Florence and Herbert Irving curator for South and Southeast Asian Art at the Met.

JOHN GUY: This is a large limestone panel which would have decorated the lower section of a Buddhist funerary mound, what’s known as a stupa.

NARRATOR: These stupas contained the Buddha’s relics and his teachings making them central to Buddhist worship. They provided essential space to deploy those teachings through imagery and narrative storytelling.

JOHN GUY: The decoration of the stupa is dominated by two motifs. One is the protective snake, the Naga, which you see coiled, poised, ready to strike in the foreground at the center of the drum.

NARRATOR: The naga was originally known in indigenous nature cults as a protective spirit. Here, the symbolic figure of protection has been captivated and persuaded by Buddhist teachings to become its shield of protection. Above it, we see a tree:

JOHN GUY: Here it appears almost as if it’s a whole canopy of umbrellas. And the reference to the tree takes us straight back to the site of the Bodhi tree, where the Buddha experienced enlightenment. So, we have both elements drawn together in one spectacular piece

NARRATOR: In this audio tour, we’ll unpack the rich symbols and stories that fill this sculptural landscape. You’ll encounter works that reference and appropriate indigenous imagery to help spread the teachings and secure the place of Buddhism in India. Enjoy your tour.

- 670. Introduction and Stupa Drum Panel with Naga

- 671. Yaksha with Lotus Vine Emerging from its Mouth

Playlist

Before the lifetime of the historical Buddha, the religious landscape of early India was already densely populated with nature spirits and demigods who occupied the trees, rocks, rivers, and ponds. These forces, personified and worshipped as cult deities, constituted the core local divinities in early India, alongside the Vedic gods of early Hinduism. The close relationship between the nature cults and early Buddhist practice is fundamental to understanding the artistic development of Buddhism immediately after the death of its founding teacher in about 400 BCE.

Shrines dedicated to nature deities were commandeered and repurposed for Buddhist use, following a wider pattern of religious appropriation of sacred sites in South Asia. Snake (naga) shrines were often chosen as sites for new monasteries. Tree shrines—sites of wish-fulfillment—were absorbed into the monastic plan. They remain a feature of daily religious life in India today. All of the key events of the Buddha’s life are associated with trees. The most powerful of these in living Buddhism sheltered the Buddha during his meditation at Bodhgaya: the bodhi, or wisdom, tree beneath which he attained full spiritual awakening.

Selected Artworks

Press the down key to skip to the last item.

Nature Deities in the Service of the Buddha

672. Sri Lakshmi

JOHN GUY: Here, you’re standing before an extraordinary image, fully realized in the round, of the earliest, quintessential, goddess of India, Sri. She’s associated with life, with motherhood, with fecundity, with beginnings.

NARRATOR: Yakshi, the female equivalent of the Yaksha, adorned the grand gateway entrances to the stupas. This particular figure stands on two lotus leaves emerging from a large pot of water, which represents abundance.

JOHN GUY: She’s at one with these extraordinary lotus plants which envelop her body.In fact, they don’t so much envelop her body as she is part of them.

NARRATOR: On the reverse side of the sculpture, about two thirds of the way up, you’ll see two peacocks perched at the center.

JOHN GUY: It’s well-known and referred to in Indian poetry that when you’ve endured the extreme heat and humidity, and when the monsoon finally breaks, it’s enormous relief for the entire community. In anticipation of the monsoon breaking the frogs come out and croak and the peacocks give out their very distinctive cry and so the presence of the two peacocks, refers to that moment when the monsoon breaks, and the land is enriched again.

NARRATOR: All this imagery and symbolism underscores the generative power of water. To have that depiction associated with the Sri Laksmi would be an explicit nod to her fundamental role in nurturing the world.

The oldest nature deities in India, male yakshas and female yakshis, were fearsome spirits to be honored and appeased with offerings of blood, flesh, and wine. The earliest surviving religious icons in India depict these powerful spirits, often sculpted at monumental scale. Many Buddhist stories tell of their conversion by the power of the Buddha’s teachings, commandeering them into the service of Buddhism. Originally malevolent deities, they assumed benign natures and became protectors of the faith. Yakshas guarded the stupas, while yakshis ensured fertility and protected infants.

According to some legends, the most powerful of all nature deities were the snake spirits—nagas—responsible for guarding the Buddha’s relics. Nagas were celebrated in the earliest stories associated with important moments in the Buddha’s life, from his first bath, administered by two naga kings, to his seven-day meditation, when a powerful naga sheltered him from a mighty storm with its body and cobra hood.

Selected Artworks

Press the down key to skip to the last item.

“When the relics are seen, the Buddha is seen.”

673. Relics from the Piprahwa Stupa

JOHN GUY: In this exhibition we’ve been very privileged to present a group of objects which are of enormous importance to practicing Buddhists, and have great sanctity, because of their association with the Buddha himself.

NARRATOR: These objects are known as relics. When the Buddha passed away, his ashes and bones were gathered, divided, and shared among eight prominent rulers of North India who placed them in stupas to honor him.

JOHN GUY:We have an assortment of objects: gemstones, coral, rock crystal, gold and silver-trimmed flower motifs, some 320 tiny objects, presented in three framed ensembles which were all part of an excavation conducted in 1898.

NARRATOR: Inspired by excavations at the time, an English estate manager, William Peppé, unearthed these relics from a mound on a private estate near the northern border of India.

JOHN GUY: He found an extraordinary, large stone coffer in which he found a whole series of reliquaries, containers in which offerings were made. One of the relic containers, had an inscription indicating that the bone and ash were those of the Buddha himself. The first such claim ever to be made based on an inscription and, of course, caused a sensation.

NARRATOR: Corporeal relics, or bodily remains of the Buddha, have the highest sanctity among practicing Buddhists.

JOHN GUY: These discoveries were of enormous importance in the history of the rediscovery of Buddhism in the late nineteenth-century in India. Buddhism had ceased to be a living religion in India by this time. It had continued in many other places, but in India it was largely a spent force for more than a thousand years.

The power of relics lay in both their concealment and their display. Most were embedded deep within the core of a stupa, never to be looked upon. Their unseen presence invoked the Buddha himself, enhancing the sanctity of the stupa and its efficacy as a place of pilgrimage. Relics were also placed on display and paraded during religious festivals, as is still done today in Sri Lanka. In the centuries immediately following the death of the Buddha, his relics were repeatedly subdivided and shared over great distances to sanctify new stupas as Buddhism spread.

Selected Artworks

Press the down key to skip to the last item.

Stupas and the “Absent” Buddha

674. Buddha footprints (Buddhapada)

DONALD LOPEZ: What we’re looking at are footprints of the Buddha with those ten square toes at the bottom with the imprint of a wheel on the sole of his feet. Footprints of the Buddha are extremely important in the Buddhist world. Footprints are, from one perspective a sign of, of past presence. That is, someone was here in the past, and we know that because they left their footprints. But they’re also a sign of a present absence. That is, the person who has left the footprints is no longer there.

NARRATOR: How do we explain that omission?

DONALD LOPEZ: The Buddha probably passed away into Nirvana sometime around 400 BCE. And for the first few centuries of the depiction of the Buddha in Indian art, the Buddha himself was absent. We call this aniconism, the lack of icons. We don’t see the Buddha represented as we know him today for many centuries after his death. And so, when he was not depicted, he was often symbolized, and the symbol was typically the seat of enlightenment. Sometimes it was his footprints. Sometimes it was a stupa. Sometimes it was a wheel.

NARRATOR: On the back wall, you’ll see him represented by a flaming pillar. These footprints and other symbols meant to represent the Buddha and his presence are seen all over the world in places the historical Buddha never visited.

DONALD LOPEZ: And so, for a Buddhist to see the footprints of the Buddha, this is something that is revered, to know that he was there as a reminder of his presence. But also, to remember that he’s also now gone, that he’s now passed into Nirvana, and this is all that we have left.

- 674. Buddha footprints (Buddhapada)

- 675. Elephants Venerating the Rāmagrāma Stupa

Playlist

The early phase of Buddhist narrative art, until around the mid-third century CE, depicted the Buddha’s presence by means of symbols, each of which had specific associations: the footprint bearing the auspicious signs of a Great Man (mahapurusa), the riderless horse denoting Prince Siddhartha’s departure from his father’s palace at the start of his spiritual journey, the empty throne beneath a tree referencing his place of awakening, the kneeling deer identifying the forest where the Buddha delivered his first sermon, itself referenced by the spoked wheel, and the parasol representing the king who rules virtuously following the laws of Dharma (cakravartin).

Each symbol evoked the Buddha’s presence in ways that devotees could readily understand, with monks providing narrative context. The sculptures in this gallery display some of the most spectacular and earliest examples of these nonfigurative signs in Buddhist art. Even when the Buddha begins to appear in human form, some of these earlier signs persist, with both types of representation coexisting for a time.

Selected Artworks

Press the down key to skip to the last item.

Buddhist Art in a Global Setting

676. The Pompeii Ivory Yakshi and the Kolhapur Poseidon

JOHN GUY: One of the reasons I organized the exhibition is to address the question of the way in which early Buddhist India engaged with the wider world.

NARRATOR: The objects in this gallery tell a story of India’s close commercial ties with the Mediterranean and later Roman world.

JOHN GUY: It’s a moment in Indian history when a very powerful dynasty was emerging in the southern regions actively engaged in international trade. One of the most remarkable objects that bears witness to this, international dimension of the Buddhist world at this time, was the object you’re looking at now which is a large-scale ivory figurine.

We’re fairly secure about where this was made, but where this was found is quite astonishing.

NARRATOR: This figure was found at the famed archeological site in Italy called Pompeii. Excavated from a rich merchant’s home, it lay beneath layers of ash from the catastrophic eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 CE. This object provides a glimpse into complex networks of luxury trade between India and the Mediterranean Roman World.

JOHN GUY: The second aspect of this is the bronze image of Poseidon.

NARRATOR: You’ll find him in the large case to your right. His arm is raised above his head as if holding a trident and his foot rests on a support.

JOHN GUY: There must have been many produced in Alexandria or in other places to put in small shrines around the greater Roman Empire.

NARRATOR: This particular bronze was probably created around the second century CE.

JOHN GUY: It was excavated with some other Roman, luxury objects in a small town in western India. By bringing together the Indian ivory from Pompeii, the Roman bronze from western India, we can present, that whole story of Indo-Roman trade that extraordinary exchange system that was operating, at its boom period in the first to the third centuries of the Common Era.

Since its early history India has been in continuous dialogue with cultural forces beyond its borders, through trade, diplomacy, and conflict. Images as well as ideas were carried along these trade routes. Early Buddhist art was shaped in part by these external influences, as Persian, Greek, and later Roman contacts left their mark on the arts of the subcontinent. India’s flourishing commerce with the Imperial Roman world in particular is well documented: black pepper, aromatics, gemstones, ivory, textiles, and dyestuffs were shipped from India's west coast ports to the Roman Empire via the Red Sea. Roman gold and silver coins, stamped with portrait images, flowed into India in enormous quantities. Most were melted down and repurposed as jewelry.

In this gallery a Roman bronze sculpture of Poseidon, excavated in India, and an Indian ivory figurine of a young woman, excavated at Pompeii, Italy, attest to the Indo-Roman trade in luxury goods that peaked in the first centuries CE.

Selected Artworks

Press the down key to skip to the last item.

Buddhist Kingship and Buddhist Patronage

677. Dome Panel Depicting a Royal Worshipper

JOHN GUY: In this panel before us, there’s no ambiguity. We’re clearly looking at a royal worshiper.

NARRATOR: A scene of pious devotion—we see a royal figure offering himself up to the Buddha.

JOHN GUY: His hands are raised in Anjali, this is the gesture of hands clasped together in respect and supplication. He has an attendant holding an umbrella over his head to indicate his royal status, attended by a princely figure with a club. I’d read that as his general, his marshal protector, and a woman by his side, his queen, his first queen and other attendants.

NARRATOR: The relief carving relays a narrative, but the inscriptions reveal how this object was made.

JOHN GUY: This is quite common to have inscriptions which mention a certain donor from a particular place, and what’s extraordinary is in some cases, we have no idea where those places are anymore. Those names have been lost to history.

NARRATOR: But here, we do. We not only know the donor, but the maker as well. The inscription tells us that this was a gift of a female pupil of a religious teacher. In early Buddhist art in India there is a great importance placed on the role of royal donors and supporters of Buddhism. Royal patronage was critical in the dissemination of Buddhism.

JOHN GUY: The other thing which is fascinating is the predominance of women donors and not only monastics, not only nuns, but also laywomen, women of the community. They played a dominant role, certainly a very prominent role as patrons of Buddhist sites.

Mention of a “world-conquering king,” or “wheel turner” (cakravartin), is made in India’s first political treatise, the Arthashastra. In this vision of idealized kingship, the chariot wheel defines the territorial expanse of a king’s domain. The concept—and imagery—was quickly absorbed into Buddhist thought, casting the Buddha as both a spiritual monarch and conqueror. For Buddhists the spoked wheel became a metaphor for the Buddha’s teachings, or Dharma. His first sermon, delivered in the deer forest at Sarnath, was memorialized in the gesture of “turning the wheel.” The Buddhist cakravartin likewise governed not by the strength of arms, but by the moral power of virtuous rule—the laws of Dharma.

The Buddhists were the first to represent this concept in Indian art: Depictions of cakravartins at stupa sites in Andhra Pradesh confirm that this imagery was a south Indian innovation. While the rulers of southern India were staunch followers of Brahmanism, many of Buddhism’s elite supporters were women of the ruling households who, alongside merchants, bankers, guilds, and other families of property, funded its monumental monastic structures.

Selected Artworks

Press the down key to skip to the last item.

Narrating the Buddha’s Lives

678. Torana Architrave: The Buddha's Birth and First Sermon

NARRATOR: Monks provided instruction and communicated Buddhist ethics and teachings through detailed imagery like these recently excavated gateways at the entrance of a stupa.

JOHN GUY: From the very earliest times of Buddhist architectural decoration, it’s very clear that they make use of storytelling. This was obviously a powerful and important tool for a community which was largely illiterate.

NARRATOR: Stupas and these grand entrances served as critical locations to share those stories.

JOHN GUY: That’s what we see at Phanigiri, an extraordinary site which has produced some extraordinarily beautiful Buddhist art from the third and fourth centuries.

NARRATOR: This is the only surviving example of a freestanding early Buddhist gateway that depicts a continuous narrative of the Buddha’s life.

JOHN GUY: What’s fascinating is that we always talk about the early images of the Buddha being represented by symbols, by the wheel, by the footprint, by the umbrella, by the empty throne and so on.

NARRATOR: Yet, here on the same gateway, we see something new and compelling.

JOHN GUY: We get the representation of the Buddha’s birth, but the Buddha is not shown. He is absent. No Buddha to be seen. On the other panel we see the enthroned Buddha, seated with a flaming pillar above him, and at his feet two deer or antelope sitting, listening. This is a very specific reference to the moment when the Buddha gave his first sermon after enlightenment.

- 678. Torana Architrave: The Buddha's Birth and First Sermon

- 679. Ayaka Cornice with Four Scenes from the Buddha's Life

Playlist

Over time, stupas became ever more complex structures. While storytelling had always been central to their decorative programs, the addition of four projecting offering platforms and sets of commemorative pillars—both distinctly southern innovations—greatly expanded the space available for narrative scenes. In circumambulating the stupa, devotees could immerse themselves in these stories, presented with picture-board clarity. In the sculptures seen in this room, which date to the third and fourth centuries CE, stories from the life of the historical Buddha, as well as those of past Buddhas and bodhisattvas, are arranged vertically on drum panels or depicted serially on long panels. Key moments in the life of the Buddha are treated episodically, and routinely represent the Buddha in human form. This passion for teaching the Buddha’s message through visual storytelling became the dominant feature of stupa decor, achieved on a scale unrivaled elsewhere in Buddhist India. Presented here are some of the most spectacular works of art of this late phase of southern Buddhist art.

Selected Artworks

Press the down key to skip to the last item.

The Buddha Revealed

680. Buddha

NARRATOR: You’re standing before a monumental image of the great teacher, the Buddha. Donald Lopez.

DONALD LOPEZ: The Buddha probably died around 400 BCE and for the first few centuries of the Buddhist tradition when the Buddha is depicted, he is absent. And then for reasons that are unclear, we see the Buddha starting to be depicted figuratively.

NARRATOR: This classic image of the Buddha is rendered in the south Indian style. The off-the-shoulder robe reflects the heat of southern India. Other key marks reflect universal signs of the Buddha. John Guy.

JOHN GUY: The image of the Buddha himself is marked by a series of what are called auspicious signs. These are the markings which distinguish a mere mortal from someone with enhanced powers. The Buddha is seen to have thirty-two such marks, and they include the forehead mark, the urna, which, as the texts tell us, is a curl of white hair between the eyes. The bump on the head, ushnisha, which is understood as a sign of wisdom very likely emanates from the way in which holy men would wear their hair. The tight curls of hair which are the direct legacy of that moment when the Prince Siddhartha the Buddha cut off his hair at the tonsure ceremony.

NARRATOR: Before you leave, pause and look at one final detail.

JOHN GUY: If you look closely at the eyes because the eyeball which is normally represented [LAUGHS] where it should be is not. It appears to be rolled up into the upper eyelid, and I would suggest to you that this detail which I’ve never detected before suggests that this Buddha is in deep meditation. This is a very curious feature and one which sets this Buddha apart as something very special.

NARRATOR: We leave this exhibition with a Buddha deep in meditation. He’s in a practice that takes us right back to the Bodhi tree, his place of enlightenment. We’re reminded of the symbols—the footprints, the figures, the trees and the serpents—that have shared the power and the story of the Buddha and Buddhist art since 200 BCE, and which continue to enchant viewers millennia after their creation.

The emergence of freestanding figurative representations of the Buddha in southern India is linked to a shift away from narrative reliefs—storytelling for monastics and the lay community—toward the veneration of the Buddha as a religious icon. The limestone Buddha images in this room, all carved in the round, date to the third and fourth centuries CE. These sculptures typically occupied freestanding shrines, the images installed in the semicircular apse. This became a regular feature of later monastic architecture. The figures display the sculptors’ careful attention to the drape of the garment over the body, with the deep fluting of the outer robe giving shape to the figure beneath. The powerful gesture of the raised left hand, accentuated by the sweeping folds of a tightly drawn robe, was likely inspired by Roman dress, images of which circulated on coins.

A new innovation, small portable metal icons, deployed for personal worship and processional use, also reflect changes in devotional practices that increasingly focused on the person of the Buddha. These portable images became an important vehicle for the transmission of the southern Buddhist style beyond India.

Selected Artworks

Press the down key to skip to the last item.