Regions

Woodlands

The process of making art in the Woodlands—as in all historical Native cultures in the United States and Canada—often had religious dimensions. Woodlands art from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries expresses beliefs passed down from ancient times and reveals the evolution of enduring forms and techniques. Its imagery represents the relationships between humans and the supernatural powers that give order to the world. Using traditional materials, artists created porcupine quillwork, finger weaving, and sculpture in wood and stone. New materials acquired through trade with Euro-Americans—glass beads, silk ribbon, silver, and wool yarn—transformed clothing, regalia, and other aesthetic forms.

"As early as the sixteenth century, Woodlands peoples traded furs and food to Europeans for utilitarian and luxury items—glass beads, woven cloth, metal tools, and guns. Conflicts increased when Europeans sought to acquire land and establish political authority. The United States government attempted to forcibly remove and eradicate Woodlands peoples. Through adaptation, resistance, and resilience, Native groups maintained distinct nations and cultures."

Jill Doerfler (White Earth Nation)

Professor of American Indian Studies,

University of Minnesota Duluth

Plains

By 1780, nomadic life in pursuit of the buffalo required that all possessions of Plains peoples be readily portable, and this defined material culture and artistic expression. Pictographic histories embellished robes, shirts, and tipis. Abstract, geometric paintings graced carrying cases, called parfleche. The materials and imagery of ceremonial regalia, headdresses, shields, pipes, and weaponry expressed spiritual power. In crisis, with the loss of the buffalo in the 1870s and forced transition to reservation life, the arts continued, ledger drawing emerged, and the powwow, a community and intertribal celebration, affirmed Native values and beliefs.

"The loss of the buffalo in the late 1870s all but destroyed Plains Indian economies, and Native nations eventually succumbed to the reservations and paternalistic domination by the United States. Policies intended to transform Native Americans into Euro-Americans by eliminating Native culture, religion, and language undermined the kinship ties at the foundation of Plains economic, political, and social structures."

Jeffrey D. Means (Oglala Lakota/Teton Sioux)

Associate Professor and Chair, Department of History,

University of Wyoming, Laramie

Plateau

The Plateau has been a dynamic trade center since ancient times. Plateau artists express varied cultural identities with woven baskets, horn bowls and ladles, stone bowls and tools, wood spirit figures, and flat basketry bags. Following the acquisition of the horse in the eighteenth century, alliances between Plateau and Plains peoples resulted in a distinct style of Plateau regalia.

"Euro-American immigration to the Plateau accelerated after the 1830s, and colonial processes, from missionary religious practices to federal authority, began to take hold. In 1855, southern Plateau tribes, including the Nez Perce, ceded more than twenty million acres of land to the United States government through treaties still in effect today. Although compressed onto smaller bases, many tribes remain on or near ancestral homelands. They continue to engage in cultural practices handed down through generations."

Laurie Arnold (Sinixt Band, Colville Confederated Tribes)

Director, Native American Studies, and Assistant Professor of History,

Gonzaga University, Spokane, Washington

California and Great Basin

One of the world's greatest basketry traditions was originated thousands of years ago by Native artists, mainly women, in present-day California and Nevada. Their works take practical and ceremonial forms. Although colonization profoundly suppressed basket production, artists revived the tradition in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The interest of collectors and ethnologists as well as basketry competitions encouraged the creativity of basket makers, and several artists achieved unprecedented levels of technical and aesthetic refinement. Makers in the region have also produced elaborate feather work, regalia, and stone sculpture.

"Beginning in 1769, Native peoples of California and the Great Basin faced waves of Euro-American invasion. Forced labor and genocidal violence occurred. Euro-Americans brought livestock into the region, destroying food sources as well as the plants used to make baskets. Native peoples survived, often by working on farms and ranches. They reclaimed lands and initiated new religions, such as the Ghost Dance."

William Bauer (Wailacki and Concow, Round Valley Indian Tribes)

Professor and Graduate Coordinator, Department of History,

University of Nevada, Las Vegas

Southwest

Distinct Native American cultural groups, each with their own highly developed aesthetic traditions, reside in the Southwest. The Diné (Navajo) are distinguished by their weaving and jewelry, the Apache, Tohono O'odham (Papago), and Akimel O'odham (Pima) by basketry, and the Pueblo peoples by a long tradition of both architecture and ceramic arts. When the transcontinental railroad opened the Southwest to tourists and travelers in the 1880s, many artists of the region produced for this new market.

"Brutal Spanish colonization began in the Southwest Pueblos in the sixteenth century. The Apaches and Diné (Navajo) warred with the Spanish, other colonial New Mexicans, and, later, Euro-Americans until they were forced onto reservations in the third quarter of the eighteenth century. Disease took its toll on the Tohono O'odham (Papago) and Akimel O'odham (Pima) in southern Arizona. The resiliency of Native peoples of the Southwest is rooted in a great respect for the inherent responsibility to care for one another, the land, and animals and to adapt to change brought on by the influence of American culture."

Brian Vallo (Acoma)

Director, Indian Arts Research Center, School for Advanced Research,

Santa Fe, New Mexico

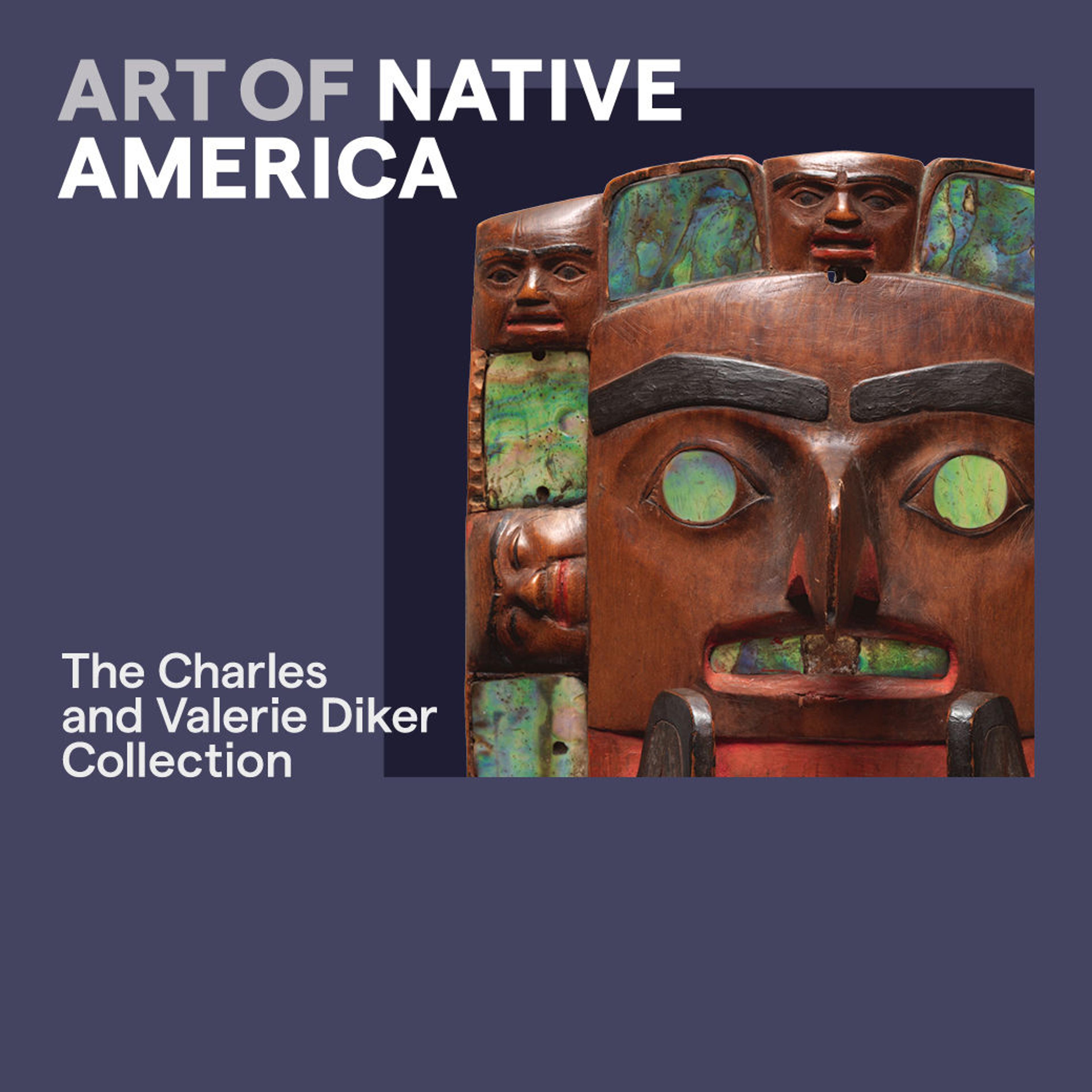

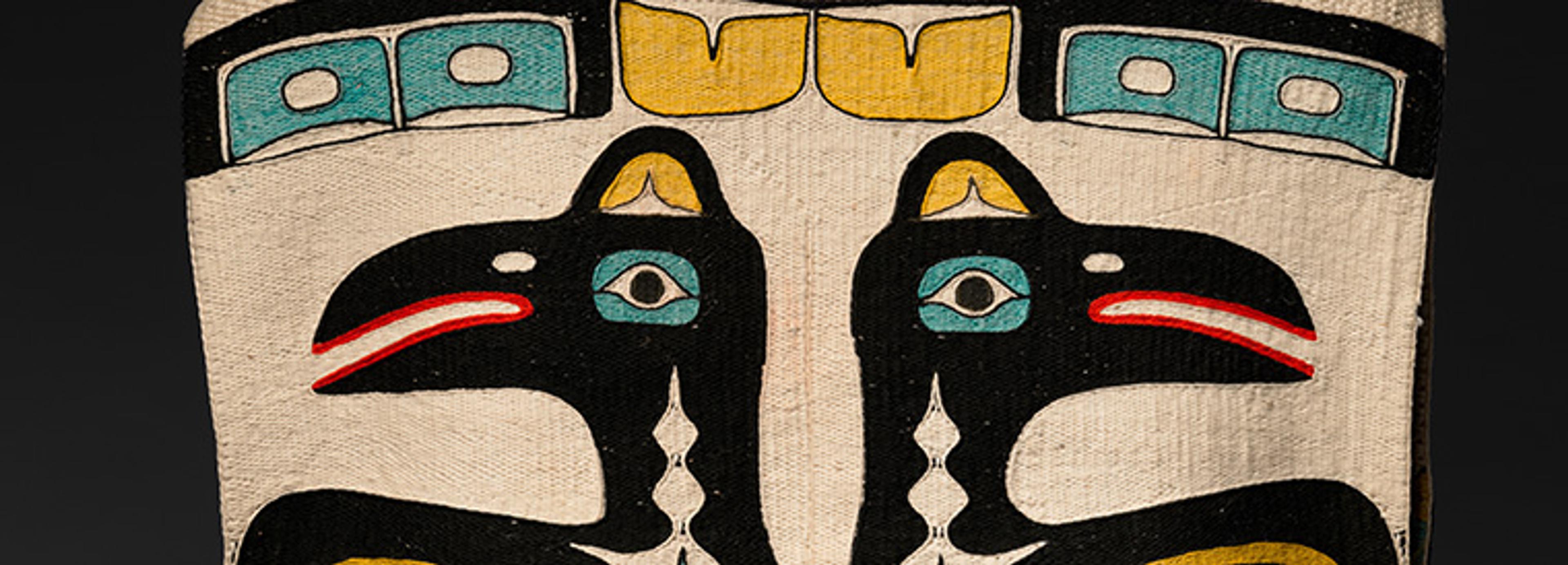

Northwest Coast

Northwest Coast cultures are known for their refined sculptural works and complex system of abstract pictorial imagery, termed formline by art historians. Consisting of ovoid forms and U-shapes within structures of continuous curvilinear lines, the distinct style is used to represent a variety of beings in paintings, relief carvings, engravings, and textiles. Artists from this region frequently make works displaying animal ancestors and clan lineage. Elaborate ritual performances affirm societal structures and origin stories. Masks, rattles, and amulets employed by shamans depict spirit beings, the trance state of the shaman as he practices, and the transfer of supernatural power.

"The appearance of non-Natives on the Northwest Coast beginning in the late seventeenth century brought both opportunities and challenges. Many peoples benefited from the maritime and land-based fur trades that generated new sources of wealth and status. However, disease and violence accompanied these entanglements. The pressures of settler colonialism came to the Northwest Coast in the mid- to late eighteenth century, later than in parts of eastern Native North America."

Joshua L. Reid (Snohomish)

Associate Professor of History/American Indian Studies,

University of Washington, Seattle

Arctic

For Arctic peoples, the boundaries between the spiritual and human worlds are permeable, and artistic forms express the worldview that humans, animals, and spirits exist in a state of reciprocal exchange and potential transformation. Yup‘ik, Chugach, and Alutiiq (Sugpiaq) makers produce elaborate masks used in community ceremonies. Shamans also employ masks in their rituals to communicate with the spirit world. In a tradition continuing from ancient times, the Inupiat and other coastal Alaskan artists create small-scale ivory sculptures and tools engraved with figural and geometric imagery.

"Starting with the arrival of Russian fur traders in 1741, Alaska became the site of colonial exploration and exploitation. Colonizing powers—Russian, French, Spanish, and British—brought deadly diseases as well as alterations to economic, political, and spiritual practices. Despite this legacy, the ideas, symbolism, and materials of the past are alive in Alaska’s contemporary arts—reflecting deep connections with the land, sacred traditions, and cultural protocols that have evolved over thousands of years."

Nadia Jackinsky-Sethi (Alutiiq/Sugpiaq, Ninilchik Village Tribe)

Independent scholar, Homer, Alaska

Themes

Art in Native Life

"The interconnectedness of everything, the symbiosis of who we are and what we do, the nexus between the intangible and the tangible, the interdependence of the physical and the spiritual—these concepts embody the whole philosophy of Native life and culture.

This philosophy speaks volumes about the relationship between Native arts and our continuance as vital and living peoples and cultures into a future that the ancestors wanted—and fought and died for—on our behalf. Let us never cease honoring their gift."

W. Richard West Jr. (Southern Cheyenne)

President and Chief Executive Officer, Autry Museum of the American West,

Los Angeles, and Founding Director, National Museum of the American Indian,

Smithsonian Institution

Loss and Resilience

"Native people endured immeasurable loss and change, yet many adapted. ... Many who did adapt also preserved their deepest traditions, their beliefs, their ceremonies, and their arts."

Arthur Amiotte (Oglala Lakota/Teton Sioux)

Artist, educator, and author, Custer, South Dakota

"We regret and mourn the drastic and sudden losses of the preceding centuries—the lands, the ceremonies, and the lives of our ancestors.

Our ancestors must have had an inner strength. As Native peoples seemed to reach the nadir of their existence, they did not die off or disappear into the larger American society. Instead, they experienced a renewed sense of creativity."

Emma I. Hansen (Pawnee)

Curator Emerita and Senior Scholar, Plains Indian Museum,

Buffalo Bill Center of the West, Cody, Wyoming

Emissaries from the Past

"Sly in their beauty, these object beings serve as emissaries from the past. As silent witnesses to violence against Indigenous Nations, these beings, as art, embody the deep knowledge of this land as evidence of cultural and ecological sustainability. The continuity of Indigenous Nations in the Americas is secure in the persistent relationship with these beings, as art, whether in the museum or in ceremony."

Jolene Rickard (Tuscarora, Turtle Clan)

Associate Professor, Department of Art History, and Director, American Indian and Indigenous Studies Program, Cornell University, Ithaca, New York

Prayers of the Makers

"These works are still serving their purpose; their lives are not complete. They are fulfilling the thoughts and prayers of their makers—and offer blessings to all the people from around the world who visit these galleries."

Brian Vallo (Acoma)

Director, Indian Arts Research Center,

School for Advanced Research, Santa Fe, New Mexico